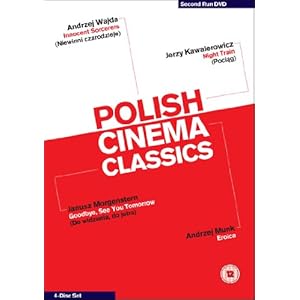

From today on, the new Second Run DVD box set, "Polish Cinema Classics", is available from Amazon.co.uk. You can find out more about this excellent edition (as well as read fragments of Michael Brooke's top-notch booklet essay on Janusz Morgenstern's Goodbye, See You Tomorrow [1960]) here.

I had the honor and the pleasure to contribute a booklet essay on Andrzej Wajda's Innocent Sorcerers (1960) for this edition, which spotrs a gorgeous new transfers of all films as well as many other extras. Below, I attach a portion of my essay, the full version of which is to be found in the DVD booklet.

* * *

(...)

[Innocent Sorcerers] is centered on the character of Andrzej: a young, hip, heavily womanizing doctor, who divides his time between his medical practice at a boxing arena, constant dating, and playing jazz in a local den where he’s known as a drummer with the stage name of “Medic”. With his bleached hair and never-less-than-cool demeanor, Andrzej is both a proto-hipster and an almost otherworldly creature of the night: always on the prowl, never taken aback by anything, forever playing the seduction game he’s so apt at he doesn’t bother much with using first names of his lovers. He comes close to being an erotic omnivore, save from the fact that he’s strictly heterosexual. It’s worth remembering, though, that – as Adam Garbicz pointed out – Łomnicki was tempted to play Andrzej as bisexual, which might have been rooted in Andrzejewski’s script (not that it would come as a surprise, considering Andrzejwski was gay himself and often communicated his largely repressed desires in his work; most strongly in his single-gargantuan-sentence novel Gates of Paradise, also filmed by Wajda in 1968).

(...)

The fact that Wajda used many actual Warsaw locations, such as the “Gwardia” stadium and “Largactil” jazz club, as well as populated his movie with a slew of real-life jazz personalities (such as Jan Zylber, Andrzej Trzaskowski and the film’s composer Krzysztof Komeda, playing a character named after himself), gave the film a distinctive, timely feel. Juicy bit-parts delivered by young Roman Polański and the forever-purring Kalina Jędrusik (as a sexy reporter making bedroom eyes to Andrzej even as she interviews him), further embellished Innocent Sorcerers and made it into a lively snapshot of the period. Even the self-consciously modern touches, such as including the film’s actual poster in its own opening shot, and making the featured radio announcer comment on “the new song from the film Innocent Sorcerers, sung by Sława Przybylska”, have a unmistakable flavor of a homespun nouvelle vague. It’s also worth noting that the shooting of Sorcerers… was simultaneous with that of Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless (1959): yet another double portrait of “immoral” youth that was about to set cinema itself ablaze.

The heart of the movie lies in Wajda’s handling of the two central characters and their milieu. Andrzej’s makeshift apartment – simultaneously turgid and hip – is masterfully established in one of the film’s earliest and longest takes, in which we get to witness the main character’s entire morning routine, lovingly conveyed by Tadeusz Łomnicki in about twenty consecutive bits of business (some spectacularly simultaneous, all equally captivating). What we see amounts to a near-ritual of habitual shaving (with what counts as the apartment’s most modern appliance: an electric razor-blade), jazz-listening, paper-reading and tape-playing of romantic conversations doctor had with a ditched date named Mirka. Throughout the scene, Andrzej manages to move around gracefully enough so as to never get entangled in the multitude of electric cords hanging down (“liana-like”, per Stefan Morawski) in all directions and from every wall.

(...)

A couple of stunning films by directors like Polański and Skolimowski aside, it won’t be until the 1970s and the arrival of the Cinema of Moral Anxiety movement that Polish cinema will become animated once again by a shared spirit of artistic and political urgency [which marked Polish Film School movement]. Perhaps not surprisingly, it will be Andrzej Wajda’s Man of Marble (1976) that will be seen as that movement’s masterpiece – centered on a young reporter Agnieszka (Krystyna Janda), whose fierce commitment to the truth and whose fearless struggle will seem the complete opposite of the seemingly complacent lives of “Bazyli” and “Pelagia”. In fact, her resistance will be rooted in their ennui. They refused to take their reality seriously; she sets out to rebuild it and make it livable again.

No comments:

Post a Comment